Tackling extreme droughts

With droughts expected to become more severe, we are working on securing a reliable water supply in a changing UK climate.

Across the world, work on climate change has focused minds on the risks and impacts of drought on water supply. We face significant but uncertain challenges from population growth and climate change, and there is an increasing emphasis on ensuring we are sufficiently resilient to droughts beyond those experienced in the recent past. In 2013, research suggested that 39 per cent of the world’s population was then at risk of suffering from water scarcity during droughts, and that this could increase to 53 per cent by 2080 if the global temperature rises by 2ºC.

HR Wallingford and other organisations are trying to understand the impacts of more severe droughts on the availability of public and private water supplies. In the UK, water companies typically used to plan to meet supply needs for droughts of a similar severity to the worst case in the past, but our work considers what would happen if they were even more extreme.

It is impossible to predict when the next drought will occur, or how severe it will be. In addition to hotter, drier summers, the latest climate projections by the UK Climate Projections 2018 (UKCP18) suggest the potential for:

- longer recession periods because of lower autumn rainfall;

- an increased likelihood of successive dry winters; and

- severe and sustained droughts over large parts of the UK.

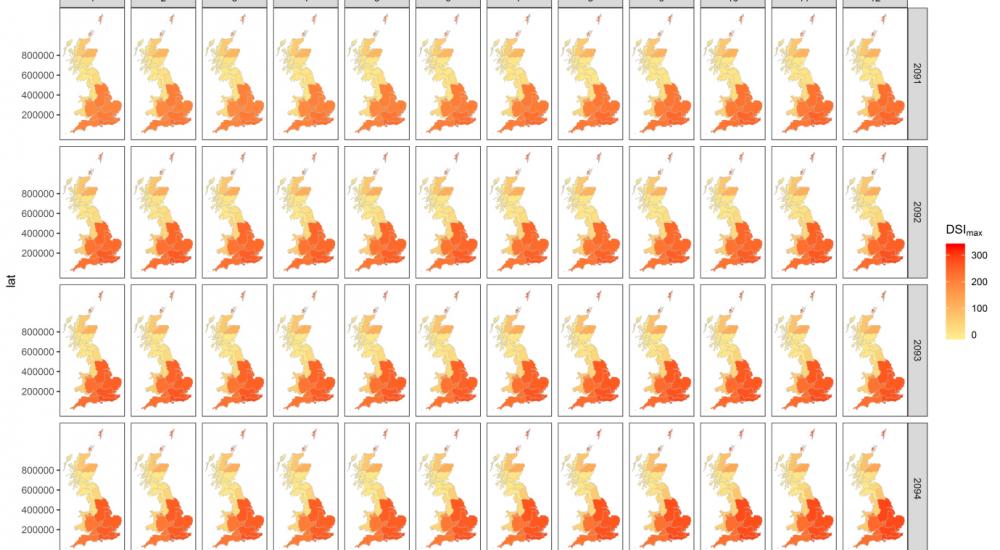

This means that it is critical that planners can understand and communicate the resilience of our water supply under a range of conditions beyond those experienced in the recent past. The figure below shows an example drought event from one of the Met Office’s latest climate model runs, with a drought severity indicator used to relate rainfall totals to typical conditions.

Example drought event from one of the Met Office’s latest climate model runs

Traditional approaches to calculating the output of sources under different droughts are being replaced with new simulation tools, such as our Kestrel modelling platform, and novel approaches. Examples of the latter can be found in EPSRC’s Stepping Up research programme and Defra’s abstraction reform study.

At the same time, the UK government’s approach to resilience is changing, with Defra and regulators more focused on understanding the impacts of drought on customers, the wider society and the environment. This includes the setting up of more of the regional water resources groups to help with water resource planning. The National Infrastructure Commission’s report in 2018 recognised the risk, and presented ideas to help improve drought resilience through a twin-track approach of reducing demand and increasing supply, including through the sharing of water.

Traditional approaches

Before working out how drought affects the water supply, we first have to understand the impacts of weather on groundwater and surface water. This is not easy to do, as some of the most severe droughts occurred before the time of routine monitoring, so there is therefore little historical data to test or calibrate the assessments. There is also limited evidence that existing legacy models properly capture physical responses during droughts. Some of the traditional approaches to assessing the impacts of a drought on a region fail to consider that it may have multiple supply systems, and therefore consider only a single source or group of sources. When considering the impact of drought on, for example, the River Thames, we have to consider regional and national droughts as well as local events in, for example, London. This is increasingly important as more options for water trading, and transfers between catchments are considered.

New approaches

Recognising this change, in 2016 Water UK published its Water Resources Long Term Planning Framework, including drought assessment work by HR Wallingford. It uses new statistical approaches to understand the resilience of water supplies under a range of different droughts – varying in length, spatial scale and severity.

This is being linked to our current research into historic droughts for the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and previous projects on the impacts of extreme drought for the UK’s Environmental Agency and UK Water Industry Research (UKWIR). By using new drought vulnerability assessments, we can present the link between length of drought and severity to stakeholders. This give them real insight into the relationship between different droughts, the subsequent risk to supplies and the potential consequences to customers and the environment.

As well as applying this to our work in UK, we are also using it in projects in other regions, such as the Caribbean, Africa and Middle East.

Moving forward

If the tools are now available to understand the relationship between rainfall (or rather the lack of it) and water supply, we believe the next stage is better integration between water resource management plans, drought plans, and emergency plans. These are currently a range of different documents, which all aim (ultimately) to achieve the same thing – securing a reliable supply of water during different types of weather, both in the near-term and into the future.

For the next round of water resource management plans, some companies are already thinking about how to better understand and present a coherent approach to planning to improve the resilience of supplies under a range of different droughts, including the more severe ones we see in the latest UKCP18 work. We are leading on this by updating the National Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA3), which will provide assessments on which to base these plans.

All this work means that we can really start to provide insights into what makes a resilient water supply, whatever the future holds.

Want to know more?